Who Is the “Noted Writer” Buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery?

The grave on which I’m lying is overstretched by the wide-spread canopy of a Japanese dogwood tree. Its fruits, which look like large, spiked cherries, lie half-squashed and rotting all around me. Nearby are a small village of markers belonging to the Schneider family, most of which seem to memorialize children who died in the early nineteenth century. The endless burring of the late morning crickets is making my head feel thick and drowsy, and a nearby chickadee is trying to tell me a joke I can’t understand.

The Sleepy Hollow Cemetery seems nearly empty today—of the living, anyway. I’ve seen a few cars go by the paved curve that wraps around this section, but I’m the only pedestrian. There was no one to take notice of me as I made my way past the acres of plots marked MOTHER MOTHER MOTHER WIFE, carrying the two long-stemmed roses I’d bought in the market at Grand Central Station.

After having jammed into two different rush hour subway cars and elbowed my way through the commuter crowds to get to my train, the last thing I expected of the day was to be so utterly alone. Even the posh, tastefully historic neighborhood I’d walked through from the station at Phillipse Manor was deserted except for occasional landscapers, faces obscured by bandanas.

A few disks of lichen, about the size of sand dollars and the pale green of oxidized copper, decorate the four names on the headstone. The surname at the top is mine.

*

The writer Thomas Beer was born in 1888 and died suddenly—supposedly—of a heart attack at the age of fifty. His mother, Martha, died a few months later. Alice, his older sister, outlived him by many decades, passing in 1981 at the age of ninety-four. Little brother Dick was estranged, buried elsewhere. Their father, William, who died in 1916, is here as well. For much of Tom’s life, most of the family was based in Yonkers, a small city about halfway between the cemetery and Manhattan.

The headline of his New York Times obituary says, “NOTED AUTHOR.” Not quite FAMOUS, not quite CELEBRATED, and certainly not WILDLY SUCCESSFUL AND FINANCIALLY COMFORTABLE, but NOTED. “Grace and economy of words marked all his writing. [. . .] Mr. Beer hated to state flatly that a thing had occurred. He preferred to suggest it by allusion.” Allusive and elusive—these would come to characterize my assessment of him as well.

I’d spent the last week in Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library going through the Beer Family Archives, the existence of which I’d been wholly ignorant when I was a student there in the late ’90s. At the time, I’d had no idea who Tom was, or that he’d graduated from Yale in 1911. My grandfather or one of my aunts might have told me, but it’s likely I took no notice. And as much as I’d like to conjure a vision of myself passing that library for four years as an undergrad, unaware that seventy-five linear feet of family history lay just beyond its walls, the whole of it was likely stored offsite in nearby Hamden. There were no whiffs of barely-heard ancestral echoes reaching out to me as I passed—only the stale dishwater steam venting from the nearby dining halls.

The truth is that strange family facts resurfaced frequently among my relatives, and often unexpectedly, treated as common knowledge by others but unknown to myself. This may be a peculiar condition of those whose parents die young; mine were both in their forties. Of the surviving adults, no one knows quite what to tell you, or when it’s appropriate to do so. At your father’s funeral? A year later, when you’re sixteen? At your mother’s funeral, when you’re eighteen? And what about your younger brother—should you be enlisted to tell him things? As a result, things come out in odd bursts, like sand-buried clams spitting little geysers on the beach.

Over a paper plate of potato salad, a cousin corrects me: “No—your father was married twice before your mother.” “Your mother dated a Black man,” my great-uncle tells me in low, confidential tones at a bar mitzvah. My great-aunt: “Your mother’s father was circumcised as an adult.” My second cousin: “Your mother threatened to leave your father if he didn’t stop drinking.”

The truth is that strange family facts resurfaced frequently among my relatives, and often unexpectedly, treated as common knowledge by others but unknown to myself. This may be a peculiar condition of those whose parents die young.So that only in my early forties I should have become truly aware of my (first) cousin (three times removed) Tom, whose oeuvre included dozens of popular stories in the Saturday Evening Post and a few acclaimed biographies, was hardly surprising. Nor was his queerness, as it became discernible in that slowly developing history. That I should have discovered through a Google search that he and his sister and parents were all buried in the legendary Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, that Jim at info@sleepyhollowcemetery.org should affirm the graves are still there, that they should be a short walk from the grave of Washington Irving and the Headless Horseman Bridge—this all seemed, to me, to be par for the course.

The cemetery sprawls with eighty-plus beautifully maintained acres of markers and monuments, and boasts more than a few historic muckety-mucks besides Washington Irving, including makeup mogul Elizabeth Arden, ur-socialite Brooke Astor, and labor movement icon Samuel Gompers. The cemetery’s website even notes that the Ramones were “buried alive” on the premises for their “Pet Sematary” video. One of the oldest sections is the Old Dutch Burying Ground, where the seventeenth-century headstones have a sullen, circumspect look, as though the sunlight touching them has been dimmed.

There are broad, occasionally steep hills, clusters of towering oak trees, and a river winding along its eastern border. From what I can recall, the cemetery in which my parents are buried is much newer and much more modest—more of a glorified football field in which geometry is the dominant aesthetic rather than the vicissitudes of landscape. The kind of place through which you can drive a riding lawnmower with ease. But I haven’t visited in over twenty years, so I don’t trust my memory to more than this.

*

In the archives, I’d been going through Tom’s correspondence with old college friends, his letters from camp during World War I, yellowing packets of photos, condolence cards to his sister, Alice, and his mother after his death, and Alice’s letters to doctors and friends during the mental breakdowns and hospitalizations in the last few years of his life. I couldn’t say quite what I was looking for, other than to get a better sense of him. But whenever I’d read a letter that seemed, for a moment, to sharpen something in my understanding, I’d feel the queasy worry that this was only superficial; could someone pull a few random emails or photographs from my life and presume to have gotten closer to my obsessions and grudges, my terrors, my joys?

If there was any certainty to be found in the dozens of boxes and hundreds of enclosed folders catalogued by Yale, it was Alice’s faithful love of Tom—not only from his exhausting mental collapses she managed and for which she secretly secured funding from his friends to treat in his last years, but from the meticulous care with which she assembled his archives.

Meticulousness was true to her nature—she’d run an antique business in New York City from the late 1920s to the mid-’40s specializing in Spanish fabrics, and then spent over three decades working as a curator for the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, whipping their antique textiles collection into shape and helping it grow. Her entire life, from the personal to the professional, seemed to have been about preserving the past and making it legible for others.

In the archives, she’d written up profiles delineating Tom’s friendships with the correspondents most represented in the files, detailing how they’d met, and when, and a little of the nature of their relationship. In going through folders, I’d find that she’d seeded some of them with brief handwritten notes annotating the circumstances behind a letter, a clipping, snapshot. An addendum to a few plaintive, semi-flirtatious letters from the gay British author Hugh Walpole observes that Tom “spent a good deal of time dodging Walpole,” and that “on the whole he tried to escape Walpole’s attentions.”

Prefacing a stack of studio photographs from the early 1930s, one of which would be featured on the cover of his selected stories, I find a note from 1941 in Alice’s measured, thoughtful script: “Mother hated these photographs . . . I think it is fairly interesting in that all show Tom’s ill health.” With condolence cards from the manager and assistant manager of the Hotel Albert in New York City, a blunt scrawl: “From the Hotel where he died, alone at night. They had not the sense to find us. —A.B.”

*

I wonder if this worry of mine—about whether someone could presume to have a true understanding of me from a few random emails or photographs—is a little disingenuous. Being a writer means that, social media rants notwithstanding, one is fairly powerless over how one’s words will be received, digested, discoursed upon—if at all. You don’t get to hover over your reader’s shoulder while they pore over the intimacies of your life and art, interjecting, No, what I meant there was—. And this is pretty much a preview of the aftermath of one’s death: you no longer get to speak for yourself. Maybe it’s because I’m not a parent, or maybe it’s because writing poetry automatically dooms a lot of what I do to obscurity and oblivion, but I can honestly say that’s never bugged me too much.

No, I think the real anxiety that confronted me in the archive was the great task that must have been faced by Alice: to shape her brother’s legacy into something lasting and legible. And it’s clear that she felt the weight of this responsibility. Every scrap of paper bearing a note in her script, every typewritten narrative augmenting the circumstances of Tom’s life and career feels like the touch of a concerned hand. And it’s certainly possible that her orchestrations of the archive were her own bid for a kind of legacy: the guardian of her brother’s flame.

But here I confront my own self-doubt that I’d be up to such a task on behalf of my own brother’s memory. I can see myself endlessly hemming and hawing over Josh’s school pictures and youth soccer team patches: what should be included? What should be explained? What truths might I gloss over or edit in the name of giving any descendants a more pleasing, empathetic portrait of him?

What should be explained? What truths might I gloss over or edit in the name of giving any descendants a more pleasing, empathetic portrait of him?Tom and Alice seemed to have been very close, both in residence and spirit. They lived with their mother for a great deal of their adult lives, and his best friends, Monty and Carey, maintained a relationship with Alice for years after Tom’s death. I try to map this against Josh and me, and realize that he and I lived together with at least one of our parents for a total of thirteen years—from his birth to our mother’s death. Then our Long Island home was sold, and he went to live with relatives in New Jersey.

I don’t think we could comment on each other’s lives across the ensuing years with the kind of detail Alice does for Tom in his archive—though I’m not saying we should be able to. There’s something about having one’s shared home emptied out that makes one feel scattered, dislodged. With our childhood memorabilia in storage units and family attics, we both spent much of the early parts of our adult lives peregrinating about the country—I following the currents of academia, he those of the hospitality industry. We haven’t lived in the same time zone in decades. The minutiae of his relationships, his sartorial shifts, how he takes his coffee—all these are the expertise of people other than me.

*

I rise from the grave. Remembering the wet-garbage quality of the humid Manhattan air last night, I take extra-deep, clean breaths. I turn back to the headstone and announce, “I’m going to go eat my lunch down by the river, and then come back.” I restrain myself from making a small bow.

The river turns out to be a creek, at best, but the sound of the water is bustling and cheering. As I chew on the remaining half of my bagel with lox schmear, I try to work out what I’m feeling. Not sadness. Respect? Maybe. A sense of having performed a duty? Certainly. The substances that were the bodies of Tom and Alice lie in the earth, but as to their spirits, I know they’re long gone—or, rather, were never here. This, I suppose, is why I feel no compulsion to visit my parents’ graves—they are much more with me than they could ever be there. My father’s guitar, which sang me to sleep so many nights, rests in a case on the second floor of my house. His leather jacket creaks on a hanger in the closet of my study.

Sometimes I wear my mother’s wedding band out when I’m going someplace I think she’d like to be. Fragments of her face greet me in the mirror every day—the dark brows, the vertical line that cuts between them and always made her look angry, regardless of her mood. And as I creep into middle age, the characteristic bags from my father’s side of the family encroach more and more under my eyes.

Something lets out a creamy twitter. Two raptors—possibly vultures—tilt high overhead.

*

Here’s the thing: any worries I might have about my abilities to craft an accurate archive for my brother, on the awful likelihood that he’d predecease me, are completely unnecessary. Tom had no long-term romantic partner—though a few of his queer friends and colleagues did, in the guise of same-sex valets, secretaries, professional managers, etc.—and no children. My brother, on the other hand, is in a loving marriage with a warm, compassionate woman, and has a young daughter whom he adores. He delights in the fact that he’s often able to work from home and be closely embedded in her life. Should the unthinkable happen, Nicole and Billie Rose are more than up to the task of collecting and maintaining the files and mementos that would shape his posthumous portrait into something real. Sure, I’d be on hand to augment and fuss: a story about this knickknack or that old shirt. But there’d be no burden on me to singlehandedly preserve him for the ages.

What is my task, I realize, is my responsibility to be an archive of our parents for Josh. Dad died when he was ten and I was fifteen, and Mom died when I was eighteen and my brother was thirteen. Sometimes, when I offer up a memory to him over the phone—Do you remember when Mom would . . . ?—he’ll respond with a flat No. And the brusque, door-shutting quality of that reply suggests that he resents the extra five years I got with them by accident of being the oldest. To have known them with a memory a little bit more developed than his, with more cubbies and drawers in which to store things.

Twenty-plus years after their deaths, my brother still has no shortage of people to talk to about our parents. As I write this, he’s just returned from a trip where he was visiting first with one of my father’s older sisters, and then with my mother’s best friend. In both cases he gained insight into Dad’s alcoholism and sobriety (how deeply the disease is embedded in past generations of our family, how Dad founded the first nonsmoking AA meeting on Long Island that’s still going strong almost forty years later).

But I can tell him about sitting on Dad’s lap in the orange chair and being allowed to slurp the foam off a beer that had been poured into a German stoneware mug, slate gray and augmented with flourishes of cobalt blue. I can tell him about building little villages with the dozens of sour-smelling wine corks that piled up in our kitchen while we lived in France when he was a toddler. I can tell him about the years of phone messages left on our answering machine by strangers with only first names (the recording was my father, reciting a self-penned rhyme: We can’t come to the phone right now, but we’d like to talk to you anyhow. We may be away or at home or asleep, so leave a message at the beep!). I can share with Josh about our parents as parents—something no one else can do. So am I doing it well enough? Honestly enough? With enough detail that’s evocative and enduring? If I’m not a good enough writer for this, am I good enough for anything else?

*

On my first day in the archives, I signed out Tom’s photo album. It was a volume that spanned from about his late teens to just after college—about 1907 to 1911. The photos all have that characteristically historic sepia tint, their corners tucked into rounded slots in thick, black paper pages. While Tom had already annotated these in ink, Alice supplemented his notes after the fact in pencil, identifying places or people, or Tom himself.

Their two scripts seem to speak not so much to each other as across each other, a pair of different voice recordings being played at the same time. In their photos, Tom has the upslanting eyebrows and narrow eyes I remember from my grandfather, his thick, shiny hair standing up high on his head not unlike my dad’s, and Alice has a calm, serious-looking face crowned with a pompadour I’d learned was red. Like Josh’s, in childhood. Like my father’s moustache. Tom and friends wear belted swimming singlets on the beach. Alice and another young woman wear vaguely nautical dresses with puffed sleeves and long dark stockings as they pose with tennis rackets, grinning (or scowling, it’s hard to tell) under poofy mob caps.

On one photo, Tom has cartooned a halo over the head of their neighbor Margot, and a jester’s belled cap over the head of his friend Jim. In a solo shot, “A.R. Wheeler,” wavy-haired, light-eyed, and leanly muscled, poses in a pair of wrestling briefs and gladiator-style sandals that strap up his thigh, his gaze direct and open, his fists nervously clenched before his hips; “wrestling weight about 122 lbs., February 1910,” Tom notes. In a suit and bow tie, Tom stands between two women with brows shadowed by flower-bedecked hats the size of manhole covers, his quizzical expression half-occluded by one of the brims as he grasps the knob of a parasol. Alice has stapled a note above it: “Tom in the centre is sneering at my enormous hat. –A.B.” Elsewhere, Alice and Tom are sitting on a summery expanse of lawn in front of a Cape Cod–style house with three slightly squinting young women—it’s unclear if they’re looking at him or the person behind the camera. On the picture itself he’s scrawled “The celebrated hair incident,” which is met by Alice’s penciled deadpan rejoinder: “I don’t remember the incident.”

There’s a picnic photo that I’d nearly passed by entirely, the shot angled such that Tom’s face, in profile, is blocked by a woman’s head, thickly braided, in the foreground. He sports a light-colored hat and summer suit, a handkerchief drooping from his front jacket pocket like a tired lily. He’s leaning into the center of the circle made by the other two women in the picture, as if dishing something out from the wicker basket to his left. They’re seated in a woodsy grove. Alice has stapled a note to the top of the page so that it’s draped over the photo like a shutter: “I don’t know where this picnic scene is or who the girls are. The man is Tom. Note cigarette in fingers—characteristic gesture—always. —A.B.”

I’d squinted close to get a better look at Tom’s left hand, extended out from his side. His forefinger and middle finger seemed slightly pressed together, but I could barely make anything out in the blurs and shadows of the old print. Only after I borrowed a magnifying glass from one of the archive librarians could I finally see the whisper of that erstwhile cigarette. Once its shape was clear to me, there was a sudden hot slick of water in my chest, as if someone drove a dowsing rod into my sternum. I felt exposed, certain that all the strangers in that venerable reading room were about to turn from their ancient clippings and slate-colored folders to look at me. I wanted the library to have provided some kind of screen or shelter for me, or at least the permission to cover my face with a long scarf, to have a little privacy in this moment.

I thought of Alice unconsciously learning the ballets and pantomimes of her brother smoking thousands of cigarettes over decades, and here was the fleeting gesture she’d known as unique to him caught on film, like a long-extinct bird. No one else would have known the cigarette was there, but even in its near-invisibility, Alice saw it and knew it and named it right away. She couldn’t bear to have it lost. I put down the magnifying glass and closed my eyes for a long time.

Could I ever go as deeply, as carefully into some remnant of our parents’ past for my brother? How many of their near-invisible cigarettes had I failed to note and catalogue for him?

Shalimar. I need to tell him Mom wore Shalimar.

*

What I remember about my brother’s most vigorous childhood tantrums is his uvula. Sometimes at the end of a particularly impassioned howl, his mouth would stay wide open, his eyes clamped shut. There would be a moment of loaded silence, and as the light hit the inside of his mouth, I would see it at the back of his throat, the nexus of all his rage and sadness contracted to a deep, glistening red drop. I recall being utterly fascinated by its clarity and definitiveness, how it trembled. I described this as part of my toast at his wedding, but I don’t think anyone got it.

*

I walk back from the creek for one last look. Standing at the grave, I hear the low, scratching sound of tires as a car passes slowly, and catch chrome winking in my peripheral vision. I feel anonymous, as if simply an ordinary part of the scenery, folded-in and unremarkable. The pair of roses I’d brought are flame-colored, to match Alice’s hair, and they lie with their stems crossed against each other. I fold my hands in front of me and try to think of something to say.

“Okay, then. Thanks.”

The track for the Manhattan-bound train at the Phillipse Manor train station is right next to the Hudson River. I look out over the boat slips to the water, listening to ropes and rigging clanging erratically against masts, as if marking time by some otherworldly system. Winds are ruffling up the river’s surface so that it resembles teeming, silvery shoals of sardines.

Next to the station parking lot, there’s an incongruously large statue of an eagle with a wingspan over ten feet wide. It’s perched on a stony-looking sphere in mid-screech, with its back to the water. Someone’s left a squat, wide candle and a broom-straw doll at its taloned feet. Remnants of wasps’ nests cluster under its wings and between its legs. The sphere is spattered and pocked with rusty decay. Still, it was clearly made with great expense and care; the primary, secondary, and tertiary feathers are all precisely differentiated, and inside its beak there’s a discernible tongue.

Though it seems to radiate historic significance, there’s no plaque or marker to explain it—it’s simply an outsized, enigmatic raptor shrieking travelers in and out of town. Later I’ll learn that it once perched on top of the old Grand Central Depot (the predecessor to Grand Central Station) over a century ago with a convocation of others, before they were dispersed to private estates and other train stations when the depot was torn down around 1910. It’s entirely possible that Tom and Alice passed under their grim gazes when they took the train to and from their home in Yonkers. But in the moment I reckon with it, there’s no language to fix it in time or context—only a half-opened beak crying out its inaudible past.

__________________________

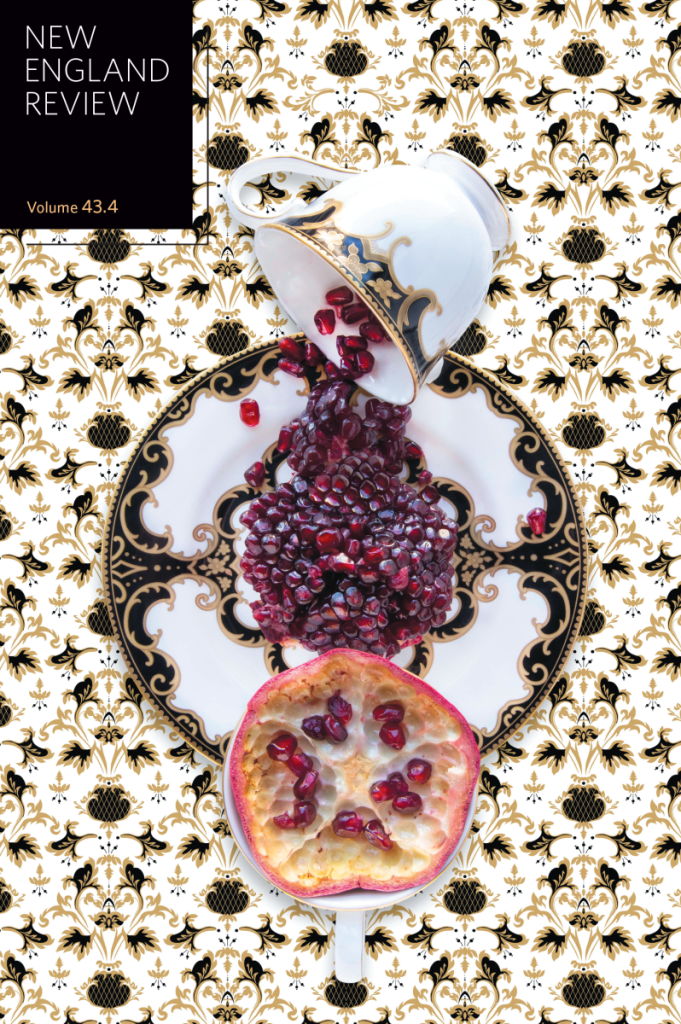

This essay appears in the new newest issue of The New England Review, NER 43.4 Winter 2022, available now.