How to Unpack a Messy World: A Reading List

If there was ever a time to develop a more nuanced view of what we humans are doing here on Planet Earth, this is it. Who among us would have believed that we’d be wearing surgical masks in the health food store, prowling the aisles, getting a shot of dopamine when we see a few rolls of toilet paper sitting on the shelf? Ok, that was me, yesterday, and the experience will be burned onto my mind until the next reality-busting moment, which will probably happen today. Nothing makes sense. As soon we heard the concept of “social distancing” we started dismantling it, piling onto Zoom screens like a very unwieldy Brady Bunch for work, school, meals, happy-hour and sex. How distant are we, really?

Writers and other artists have always explored the boundaries of who we think we are, moving us toward every kind of edge by the stories they tell, the language they use, and the forms they employ. It’s hard for to remember how surprising it was when Raymond Carver revealed the glowing hearts of his working class heroes of few words. Or how Anne Sexton’s insistence on referring to herself as a “wife” and “mother” in her poetry was a subtle and radical play on how we understand womanhood and art. Remember how much we resisted “reality TV” when it first appeared? I do. Today, I’m an unapologetic Real Housewives devotee. People who know me as a Zen practitioner that I am think I’m being funny or ironic by my love of the franchise. But what could be more dharmic than watching groups of women relate to each other and age IRL, surgical and non-surgical interventions notwithstanding? Trust me, these housewives are very real.

Which is to say, even before the utter hands-thrown up truth of today, I’ve always been drawn to the way ideas and genres overlap, and to people and experiences and art that don’t follow the rules, not because of an academic challenge to norms, though all of that can be interesting, but because of the way such art better reflects reality. Like the Japanese notion of wabi-sabi that prefers the broken line, the imperfect circle, the authentic over the polish, I’ve always liked my world funky, and my books especially.

The books I’ve gathered here are all wonderfully funky memoirs with a passion—books that do more than tell a life story, but unpack a messy world. These are books that simultaneously teach us about what it means to be human, and unsettle every notion we have about what it means to be human.

Before attempting my own hand at such a book, I never could have imagined how difficult it is to move in and out of implicit and explicit memory, emotional narrative and rigorous research, past, present, and conjecture. By expertly braiding their own deeply personal experiences into what they’re learning about their subject of choice, these writers not only share their new corner of understanding with us, but a new self-reality. I admire these five writers so much not just because they’re gifted storytellers with brilliant minds, but because of the way they make me feel: at ease in the liminal.

*

Gretel Ehrlich, This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland

I tend to be a repeater of experience rather than a seeker of new things, and I’ve kept this quiet, shimmering masterpiece next to my bed for so many years I feel truly imprinted by it. Before writing this book, Ehrlich had been struck by lightening—twice—and so she “originally traveled to Greenland…not to write a book, but to get above the treeline,” which she felt soothed her stricken heart. She soon became obsessed with the ice, the rough, dark, primitive life of the people there, and their deeply ritualized traditions, much of which, of course, has since become totally undone. She travels to and from Greenland seven times over a period of years as “the ice cap itself was a siren singing me back to Greenland, its walls of blue sapphire and sheer immensity always beguiling.” And while Ehrlich “made it a practice to travel alone… in a country of no roads, where solitude is thought to be a form of failure,” she was never alone. Not only was she “passed from friend to friend, village to village… and slowly climbed the icy ladder… to the far north,” she traveled with the Danish explorer Knud Rasmussen’s historic journals always near. The two are on a heroic expedition together.

In addition to thrilling writing about a modern life with dogs, whale-hunting, fur, sleds, blubber, seal oil, and months of frozen darkness, interwoven with a riveting history of the largest island in the world, readers will travel with one brave woman on a spiritual search who “for seven years… used the island as a looking glass: part window, part mirror.”

Andrew Solomon, Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression

While it’s often true that genre-busting work I’m drawn to is written by women, Andrew Solomon’s work is awe-inspiring in its combination of fierce intelligence and compassionate wisdom. Though he writes that “this is an extremely personal book and should not be taken as anything more than that,” Noonday Demon, published almost twenty years ago, remains the resource on the human condition of depression, clinically, historically, and personally. What exactly is depression, you ask, seeking a definition, and to know where you stand right away? No such luck, thank goddess. Instead of a clinical view, according to Solomon, “Depression is the flaw in love,” and “it is my experience that the hard numbers are the ones that lie.”

The book opens with Solomon’s vivid and heartbreaking description of his own series of breakdowns. He walks us through the high-anxiety, anger, listlessness, the profound wrong-ness of the experience of his depression, “as though you were constantly vomiting from your stomach but had no mouth.” Because we believe him, we’re more than willing to follow him through the intricate histories, nations, and treatments he discovered firsthand in his five-year journey into the many worlds of depression. “It is the walking-death quality of depression that I have tried to eliminate from my life; it is as artillery against that extinction that this book is written.”

Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich, The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir

When we meet Marzano-Lesnevich she is a 25-year-old Harvard Law student passionately opposed to the death penalty. She’s just gotten off plane in New Orleans where the air felt like a “hot wet slap” for an internship with a law firm defending those accused of murder. On her first day she watches a taped confession from a convicted pedophile named Ricky Langley who is accused of killing a six-year-old boy. By the end of the book, she’s teaching writing at Harvard. That’s how much this first case so consumes her, changes her, and transforms the way she understands not just the law, but her entire life. “This tape brought me to reexamine everything I believed not only about the law but about my family and my past.”

In a “game of telephone [she is] playing with the past,” Marzano-Lesnevich wonders aloud if “maybe to understand is to go back to the beginning.” She meticulously leads us up to the day Jeremy was killed, including the crime itself and some of its edges of mystery that remain. We learn about own Ricky’s traumatic history, conceived while his mother is in a full-body cast (I know!), and the vivid pain of the violations Marzano-Lesnevich herself suffered over many years. Doubting whether she will ever reach the beginning or end of any one point of suffering, she asks, “What happened after my memory ends? What fact does my body hold? I don’t know. I will never know.”

When she finally meets Ricky face to face at the end of the book, we’ve all been through a lot. We long for clarity about who’s good, who’s bad, and where our allegiances should lie. We so crave resolution. But this author is too wise to give us what we want. Instead, she realizes that “the man who sits across from me is a man. He’ll never be all one thing or the other. Only a story can be that. Never a person.”

Sarah Broom, The Yellow House

One of the most intriguing parts of Broom’s spectacularly passionate memoir is the fact that she doesn’t appear in full view as a character until page 117. It’s true that she has a family of 11 brothers and sisters to describe (she’s the youngest), her parents’ lives, and her father’s death, when she’s just six months old. And there’s New Orleans, the setting in which the main character—the yellow house—is born, lives and tragically dies. This is not the New Orleans of French quarter romance, but the part of town called East New Orleans, which is “fifty times the size of the French Quarter, one fourth of the city’s developed surface. Properly mapped, it might swallow the page whole.”

And indeed, this entire book is more a smart map pointing toward discoveries just off the page than a linear tale, which is of course, what life is like. As Broom writes, “My growing up world contains five points on a map, like five fingers on a spread hand.” The points are her grandmother’s house, a local road, the pastor’s house, her school, and her yellow house, about which her mother often says, “You know this house not all that comfortable for other people.” And while Broom responds, “the house was not all that comfortable for us, either,” it was the home her father built, piece by piece, and that lovingly sheltered her large family. At the same time, the yellow house also exposed them to the elements, cockroaches and shame. “These are the places that make my growing-up world.” And it’s—by any measure—a loving world that prepared her to be the kind of person who can write a book like this. We should all be so fortunate.

After East New Orleans drowns in the broken levees of Katrina, the yellow house is demolished. Broom writes, “The house contained all of my frustrations and many of my aspirations… I had no home… I understood then, that the place I never wanted to claim had, in fact, been containing me.”

Jenn Shapland, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers is one of those books I used start reading again as soon as it finished. I’ve also combed through all of McCullers’s “other” work as well, and all the biographies and letters. So I thought! When I saw the title of Jen Shapland’s book I had that simultaneous envy/panic/lust feeling, like omg I want to write my autobiography of Carson McCullers. When the book arrived, I was prepared to find it a bit too intellectual or just not that interesting. I was ill-prepared. I read this beautiful, spare honest story in one sitting. I couldn’t get enough of this woman’s quest to reveal the truth of McCullers’ life and love. And thus, her own.

The story begins when Shapland was working as an archival intern, and comes across McCuller’s letters. “I wasn’t expecting love letters,” she writes. “Annemarie’s handwriting filled the page… Carson, child, my beloved… Did that mean what I think thought it meant?” The topic of McCullers’ sexuality has been discussed, certainly, but the fact that she was married (twice) to Reeves always seems to lead the narrative in a hetero direction, though all signs point elsewhere. Shapland moves into McCullers’ childhood home on Stark Avenue in Columbus Georgia, which is now a museum of sorts, where she reads Carson’s letters, lining them up against what else has and has not been written about her and of women who loved women in the past, and wonders, “if Carson was not a lesbian, if none of these women were lesbians, according to history, if indeed there hardly is a lesbian history, do I exist?

And then she calls her girlfriend.

Back and forth she goes—seeking solace and truth through the lens of another. It can be a dizzying ride, to be asking these big questions of the world and ourselves. But in the end, as Shapland writes, “I think I knew what I wanted, though, from Carson: recognition. A rendering of my own becoming. A love story I could believe.”

__________________________________

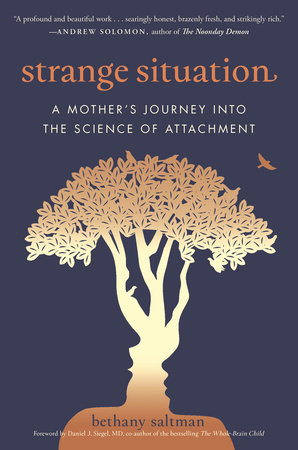

Bethany Saltman’s memoir, Strange Situation, is out now from Ballantine.