A Bizarre Pattern of Bridges: How—and Why—Baudelaire Showed Up Throughout My Fiction

I don’t think there are any rules when it comes to how one should use literary references in works of literature, except, perhaps, that they should have a life of their own.

The facts are I’ve written a short story collection and named it Evil Flowers, obviously a reference to Charles Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil. I wrote these short stories in a state of objection: I objected to the idea of the short story as an artistic achievement, where the perfection of every detail creates a meticulously built nutshell, to put the meaning of life into. I sought something different.

I was interested in how the mind works when it doesn’t really work, when it doesn’t really think, how thoughts wander, how associations lead you off trail, and back again, and off again. I wanted texts with a looser texture, with a zig zag structure, with digressions and different voices interfering with each other’s narratives. I wanted bursting fits of aggression, sudden and far-fetched associations, and I wanted slow rivers of thought, and if I was walking across a forest of symbols, I’d prefer the symbols to be close to clichés, and the characters trying, half-frustrated, to interpret them as they went along. So, three little questions arise: Why put Baudelaire in there, whose meticulously built sonnets were everything my zig zag stories would not be? And how? And would he object?

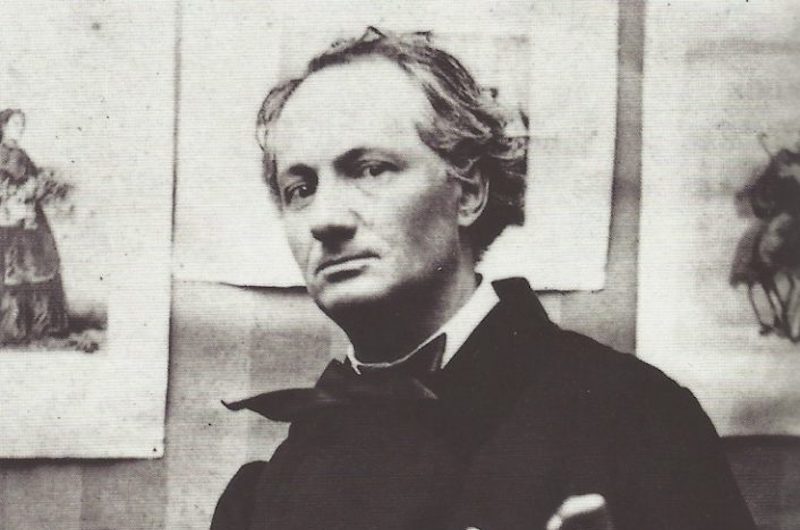

“How” is the easiest question to answer—I can simply count the ways he appears: 1) as a quote, 2) as an image (the photograph taken by Etienne Carjat in 1863), 3) in an angry discussion on how to use photographs in texts and what texts are supposed to be and what his expression in the photograph really says 4) as a reference in the title and 5) in a hidden, but pretty determined finger pointing at his essay “On the Essence of Laughter.”

Three little questions arise: Why put Baudelaire in there, whose meticulously built sonnets were everything my zig zag stories would not be? And how? And would he object?So then, why Baudelaire? His angry gaze on the author portrait taken by Etienne Carjat in 1863 entered my life the day I was going to buy a Christmas present for my younger brother. My brother was one of my favorite writers, just that he hadn’t published anything yet—he was nineteen, I was twenty-one. I had studied comparative literature at the university of Bergen for a year and was in a very strange state of mind. The semester was over, the exams were done, I could go home to my parents for Christmas, but I stayed in the room I rented for a couple of weeks more to finish the first draft of my first book, which was not going to be a collection of short stories as I’d always planned it to be.

It was snowing and I think I’d say I had had an epiphany; I was feverishly writing down poems. I had been walking across a street, and I suddenly knew the following to be true, so I wrote it down: Life / is that Lion’s Mane Jellyfish / brushing my thighs / as I swim. / Literature is the trail in the water / behind me as I / run, screaming, / ashore. And I wrote a poem I entitled “I’ll Be a High School Teacher When I’m Done Kissing” which was like this: I imagine / that if I kissed you / hard enough, overlapped your mouth / completely and sucked as hard as I /could, your tongue would loosen /and your heart would follow / at the end of a steaming / red thread / –

I wrote a poem where I compared myself not to a summer’s day but to a snowplough, rusting in a forest, and I wrote a poem about the old Norse hero Gisle Sursson, famous for having kept on fighting with his sword in one hand, although his belly was cut open and his guts spilled out on the ground: Gisle Sursson /held his guts to his chest /as a good hand /of cards/although he knew/he was dying/he held tight[1]. I stood in front of the poetry shelf at the university bookstore and looked at Arthur Rimbaud’s Illluminations.

I’d read one of his poems in a poetry class earlier that autumn that had stayed with me, “The Bridges.” first it stayed with me as something completely incomprehensible, fleeting and elusive, an almost absurd painting of non-existing bridges created by the meeting between light and water over a river (“Crystal-gray skies. A bizarre pattern of bridges, some of them straight, others convex, still others descending or veering off at angles to the first ones, and these shapes multiplying in the other illuminated circuits of the canal”[2]), where the only development was that this image was destructed by a “white ray”—but later I realized that it carried the feeling expressed in all the above cited poems: that life was an illusion, that the illusion needed to be torn down, but still, that there was something burning, living, and breathing, an objection, a protest, quite similar to the feeling I’d had, as long as I’d known myself.

I felt my brother should read him too, as I knew he was not interested in rules but how to break them, but when I read the text on the back of Illuminations, about Rimbaud’s life, which was much wilder (drugs, running away constantly) than the life I wished to influence my brother to have, I decided to keep the book myself, and picked up Baudelaire’s Prose Poems instead.

I don’t think (or maybe I kind of do) that he would object to being a prop in my texts, because even though wisemen tremble when they laugh, real gods do not.I’d read Baudelaire too, with less interest. As touching as I did find the metaphor of the poet as an albatross, clumsy ashore but with a gigantic span of wings in the air, it did not squeeze my soul. But there was one poem I remembered, from the prose poems, “The loss of a halo”, where a poet talks to another poet about how he lost his halo, crossing the street: “Just now, as I raced across the street, stomping in the mud to get through that chaos in motion where death gallops at you from all sides at once, my halo slipped off my head and onto the filthy ground.[3]”

I read it as the poet losing his poetry-halo down into the prose-mud, and this was the kind of halo-losing my brother would be interested in, I thought, so I bought both books. Rimbaud for me, Baudelaire for him. But there was a preface. And in that preface, there was a poem by Richard Brautigan about Baudelaire. It was called “The Flowerburgers, part 4”, and it was like this:

Baudelaire opened

up a hamburger stand

in San Francisco,

but he put flowers

between the buns.

People would come in

and say, “Give me a

hamburger with plenty

of onions on it.”

Baudelaire would give

them a flowerburger

instead and the people

would say, “What kind

of a hamburger stand

is this?”[4]

This, of course, was the kind of hamburger stand I’d been looking for with my poems, and it was very clear to me: I needed the lost halo, and I needed the flowerburgers, and I needed the irritated question from the people demanding hamburgers. I would just have to find something else altogether for my brother, and I walked out of the bookstore with these two books under my arm, a bit oblivious to the fact that exactly these books have been said to represent a big bang of modern poetry, and that my writing would be changed forever by them. And, naturally, this was also the big bang of the creation of “Baudelaire” as a reference in my own short stories, thirty years later.

Would Baudelaire object to being a reference? I think not, and here’s why: When Baudelaire is handing out flowerburgers in Brautigan’s poem, he is both doing what he once did, when he was alive, and writing; disrupting the stability of the common sense of a classical hierarchy of truth and beauty, a disruption Brautigan’s poem is mimicking—and creating—on its own by debasing his wonderful poems into burgers.

In both cases there is a sense of a need of disruption, and I think of the Danish poet Inger Christensen, who has said, “We could perhaps also imagine chance as a diffuse source of energy, which just by being present has an ordering effect, a kind of collaborator into our own production of order. And we could imagine that we got, through this collaboration of chance, a protection against our own overproduction of order.”[5] I sometimes think that that’s one of the things literature has to offer to society; a protection against our own overproduction of order. “What good are Baudelaire’s burning eyes, when it said on the packet you’d get glossy hair!”, says one of the lines in the last text in Evil Flowers.

“Baudelaire is the first visionary, king of poets, a real God! Unfortunately he lived in too artistic a milieu, and his much vaunted style is trivial. Inventions of the unknown demand new forms,”[6] wrote Rimbaud of Baudelaire, in one of his so-called “letters of the seer”. He added his own poem “Squattings”, which during nine stanzas of perfect metric verse follows a monk in a monastery squatting over his chamber pot, sweating, and moaning, and struggling to relieve his body from its excrements—until he, in the last stanza, is finally relieved.

The poem is a caricature of modern poetry, criticizing the dissonant relation between form (the beautiful sonnet) and content (the harshness and ugliness of modern life—“if you see dirt, you must give dirt”, as he also says)—creating the very essence of caricature that Baudelaire so luminously describes himself in his essay “On the Essence of Laughter”. There he describes how he comes across an English pantomime performance, and a Pierrot who is thick and short and who has exaggerated every part of his appearance; his lips are prolonged by two long, red bonds that make it seem like his mouth reaches his ears when he laughs, and when he tries to steal from a cleaning woman, he not only empties her pockets, he tries to put the sponge, the broom, her bucket and finally the water in his own pockets.

To make a caricature you must exaggerate the defining traits, and it is Baudelaire’s point that the laughter created by the caricature is not merely an effect, it is an art—what he calls “absolute comedy”, where the idea and the form are one. The wiseman never laughs without trembling, says Baudelaire, and both that sentence, and indeed the essay itself, has been one of the guiding lights through my writing life.

And so I don’t really think, as one of my narrators suggests, that Baudelaire would object to, for instance, the fact that I use his photograph as a text, interpreting his gaze as sulky and insulted, looking at me, the writer, angry because I’ve used his title the way I’ve used it, making it more concrete and simple (and a bit stupid in its simplicity; Evil Flowers has one meaning; these flowers are evil, while his own title, The Flowers of Evil, rather creates beauty—poetry— growing out of “evil”). I don’t think (or maybe I kind of do) that he would object to being a prop in my texts, because even though wisemen tremble when they laugh, real gods do not.

No matter what, concerning my own writing of these stories and the attempt to find a “zig zag structure”; to fling in his angry gaze was really, in its moment of creation, a momentary impulse, a certain “zig” in the line moving between form and destruction of form. So, there you go, “how and why Baudelaire” has a very simple answer, and that answer is: writing.

*

[1] All poems from Slaven av blåbæret, Det Norske Samlaget, 1998.

[2] Arthur Rimbaud, Illuminations (translated by John Ashbery), Carcanet Classics, 2018

[3] “The Loss of a Halo”, by Charles Baudelaire, translated by David Lehman, The American Scholar, 2014

[4] Richard Brautigan, Trout Fishing in America, The Pill vs the Springhill Mine Disaster and In Watermelon Sugar, Mariner Books, 1989

[5] Inger Christensen, Hemmelighedstilstanden, Gyldendal 2000,—quote translated by Karin Kukkonen https://hasard.hypotheses.org/5038

[6] Arthur Rimbaud, Illuminations and Other Prose Poems, (translated by Louise Varèse), New Directions, 1957

_____________________________________

Evil Flowers by Gunnhild Øyehaug (translated by Kari Dickson) is available now via Farrar, Straus and Giroux.